Germany - Fossil of the Year 2009 - Juravenator Starki: Dressed for Hunting

By Nando Musmarra and Dean R. Lomax

PaleoArt by Nobumichi Tamura & Mo Hassan

The holotype specimen of Juravenator starki is housed in the Eichstätt Jura Museum, the same repository where Archaeopteryx no.5 shows his feathers. To date, J. starki is one of the best and most complete theropod dinosaurs ever discovered in Europe.

Due to the exquisite fossilisation of this small dinosaur, the 1.000 members of the German Paleontology Society (Paläontologischen Gesellschaft) chose this juvenile coelurosaur (or ‘raptor’) as the well deserved winner for the 2009 "Fossil of the Year" award. Juravenator was a worthy successor over the German Parapuzosia seppenradensis, the biggest ammonite ever found.

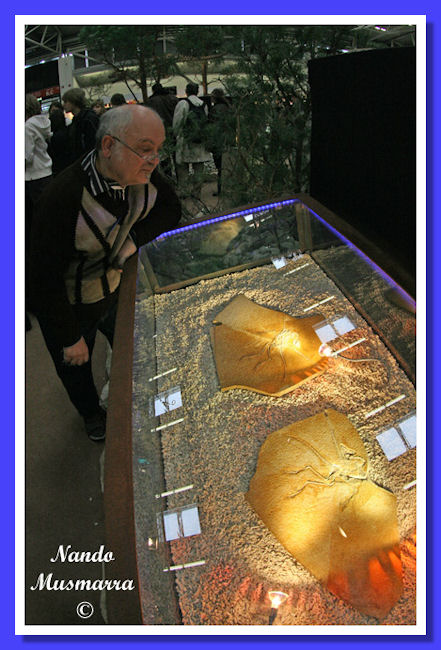

Eichstätt Jura Museum - The co-author Dean Lomax is working at Archaeopteryx no. 5 (original specimen) before 2009 Munich show - www.paleocritti.com

Actually, this small predator was found during the last century. In 1998, Klaus-Dieter Weiß and Hans Weiß, two brothers and amateur palaeontologists were volunteering for the Eichstätt Jura-Museum. They were part of a team that was conducting scientific excavations in a Solnhofen plattenkalk west of Schamhaupten (South Germany), this quarry belonged to the Stark family. During this excavation, both of the Weiß brothers made a sensational discovery in a limestone slab; here the slab contained a small theropod dinosaur skull.

The dinosaur discovery was a well-kept secret for several years. The slab that contained the skull was highly silicified, and needed careful preparation to unlock this fossils mystery. At first the specimen was placed under X-ray and CAT-Scan, in order to find the rest of the animal’s body, the results were disappointing; nothing was detected, assuming the dinosaur's remaining skeleton was lost forever. After 5 years spent searching for a new preparation technique, the new Jura Museum director decided to proceed with preparing the specimen in a more traditional way, assigning the big slab to be prepared by the expert preparator Pino Völkl-Costantini (now at Solnhofen Bürgermeister Müller Museum).

3 years and 700 hours of fossil preparation later…Pino, paying close attention to preserving even the smallest details, quite literally pulled out of the slab a wonderful and most perfectly preserved, fully articulated theropod dinosaur. Pino's careful preparatory work was extremely useful. The preparation of this specimen not only revived this dinosaur from its tomb, but enabled its first scientific description1 by palaeontologists Ursula Göhlich (at that time at Paläontologisches Museum in Munich, now at the Natural History Museum in Wien) and Luis Chiappe (Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County) in 2006.

Pino Völkl-Costantini and Archaeopteryx no.5 (original specimen) during the Munich show (2009) - Photo Nando Musmarra

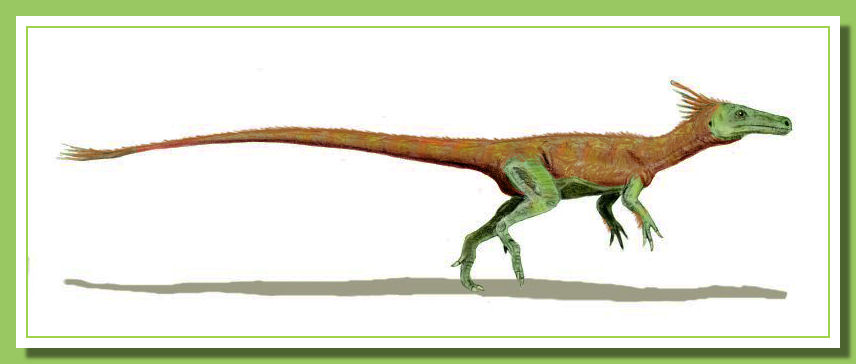

Juravenator possessed a very long tail and was in the size range of a goose (70-75 cm.). It has been established this specimen was a juvenile when it died. The small raptor was a bipedal carnivore, and likely an active hunter with powerful claws for holding its prey. This "Jurassic hunter" was finally introduced to the public as Juravenator starki. The meaning of the name: Jura after the Jura Alps where the Jurassic stage was first identified by Alexander Brongniart; venator, in Latin, meaning hunter, and finally starki after the Stark family, owners of the Stark Quarry. He was nicknamed Borsti (a German word for bristle haired dogs).

Juravenator lived around 150 million years ago in the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian, Painten Formation); this area was once an archipelago composed of small islands with a shallow warm tropical sea. As an adult, Juravenator would have been larger than the slighter older Archaeopteryx. Its diet would probably have composed of lizards, insects, and perhaps even Archaeopteryx ‘chicks’.

Some of the fossils found in the Solnhofen limestones do not belong to organisms that live in the coral reef or in the Tethys Ocean, but are rather those who inhabited the nearby small islands. In all likelihood, Juravenator was probably transported into the lagoonal environment through the process of violent storms or turbidity currents. After such an event the muddy sediments would slowly begin to build up on top of Juravenator, thus burying but protecting the dinosaur for the process of fossilization. The result is an extraordinary state of preservation7.

Solnhofen scene before Juravenator's discovery: Compsognathus, Archaeopteryx and Rhamphorhynchus - PaleoArt by Mo Hassan

Juravenator , together with Compsognathus and the recently discovered Xaveropterus are the only known non-avian theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic Solnhofen lithographic limestones. J. starki is exquisitely preserved and nearly complete from the snout to the tail (missing only few caudal (tail) vertebrae at the end of the tail); it was considered to belong to the family Compsognathidae. The surprising lack of protofeathers and the presence of large and well preserved soft tissues along the legs, tail and part of the hips show unmistakable similarity seen in the scales of primitive theropods and unfeathered dinosaurs1. This probably caused Göhlich and Chiappe major headaches when trying to identify this animal’s origins.

Later in 20062, Göhlich, Tischlinger and Chiappe published a complementary paper reporting several faded impressions of some kind of filament along the tail2. The debate amongst scientists was fierce. Palaeontologist Xu Xing doubted the compsognathid origin of Juravenator based upon the scales preserved along the tail (nevertheless Xu offered Chiappe and Göhlich a way out). Xu suggested the presence of scales on the tail could show the feather coat of early feathered dinosaurs was far more variable than seen in modern birds3. Xu was followed by Butler et al. (2007) who inferred that Juravenator was not a compsognathid, but rather a basal member belonging to Maniraptora4 (a clade including dinosaurs such as Velociraptor).

Juravenator reconstruction with protofeathers - PaleoArt by Nobumichi Tamura

Using the same ultraviolet light technique developed early in 2010 by Hone et al.5, Chiappe and Göhlich finally uncovered soft tissues with thin protofeathers of Juravenator. It was clear there was a definite similarity with those covering the Chinese dinosaur Sinosauropteryx. The simultaneous presence of both scales and protofeathers covering a small part of the Juravenator body may indicate feathers appeared on certain parts of dinosaur’s bodies before others. Chiappe and Göhlich finally provided a complete and detailed study of Juravenator’s morphology and osteology, concluding that Juravenator was similar to Compsognathus than to other groups. In comparison with Compsognathus, Juravenator has numerous unique morphologies and bone proportions that distinguish the two taxa6.

Juravenator starki adds new light to the poor record of small-bodied, Late Jurassic theropods. The skull and skin details are poorly understood in other basal coelurosaurian theropods. Thus such exquisitely preserved specimens as Juravenator contribute significantly in understanding the evolution of this clade.

Tired by words? Let's look at snout-to-tail pictures

The skull of Juravenator is characterized in having few maxillary teeth and lack of a premaxillary-maxillary diastema. The scleral rings of Juravenator show similarities with nocturnal birds, suggesting that perhaps Juravenator may have hunted at night - Photo by Nando Musmarra

Close up of the beautifully preserved and serrated maxillary recurved teeth - Photos by Nando Musmarra

Note the extremely thin and stiffened cervical ribs along the neck vertebrae (characteristic of all compsognathidae). These cervical ribs reinforced the neck, and enabled a greater motion of flexibility in the neck of Juravenator - Photo by Nando Musmarra

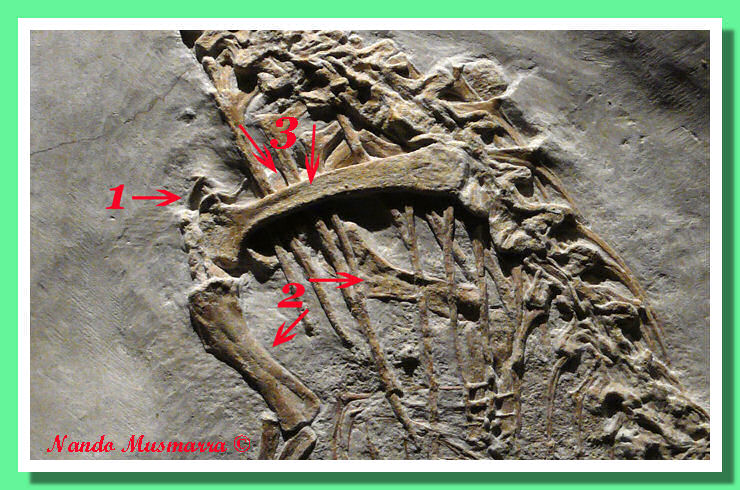

Juravenator pectoral (chest) region: 1) Clavicles (fused to form a furcula) - 2) Upper arm (humerus) - 3) Scapula: note the elongate scapula and a proportionally shorter humerus - Photo by Nando Musmarra

Juravenator gastralia (belly ribs) - Gastralia seen in Juravenator is nicely preserved; the gastralia supported the stomach of the animal. The highlighted section shows part of the respiratory muscles like those of living reptiles. Also, note the beautiful detail of the claw - Photo by Nando Musmarra

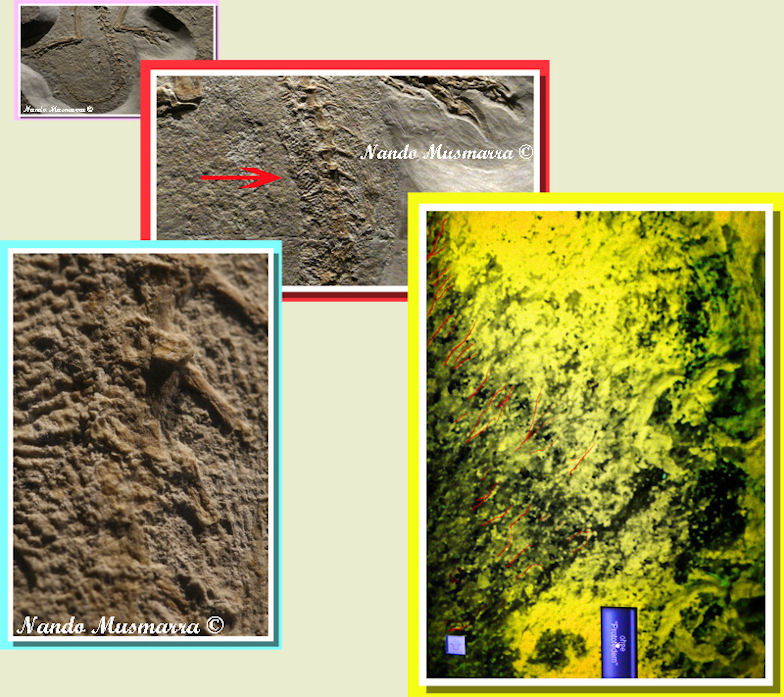

Hand claws: Juravenator like most theropods had three powerful fingers, reinforced by sharp claws. In the edited photo, the colour contrast and high saturation allows clear visualisation of the sharp claws of Juravenator - Photo by Nando Musmarra

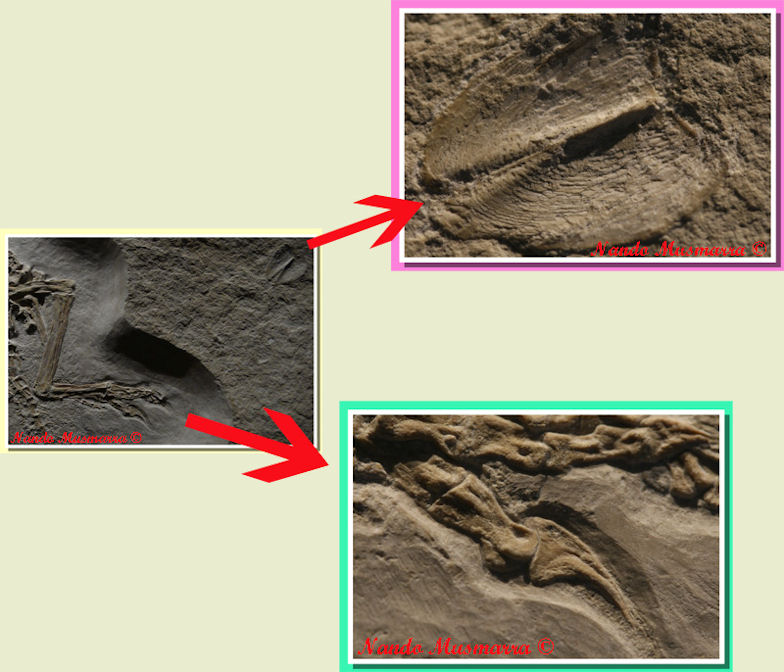

Upper photo: Few inches from the foot of Juravenator, lays an aptychus (jaw apparatus) of an ammonite, demonstrating the marine environment surrounding the archipelago - Photo by Nando Musmarra

Lower photo: Juravenator foot has four toes. Only three of those reached the ground when walking. The inner toe possesses a strong, long and sharp claw. The claws of Juravenator were able to move up and down; movements in other directions were restricted by the structure of the foot - Photo by Nando Musmarra

Several features of Juravenator indicate this specimen was an immature individual. The neural spines of the tail vertebrae were not fully formed (indicated by the lack of sutures). Coupled with the proportionally large skull and big eyes, and the incomplete ossified surfaces of multiple bones indicate that Juravenator was young when it died - Photo by Nando Musmarra

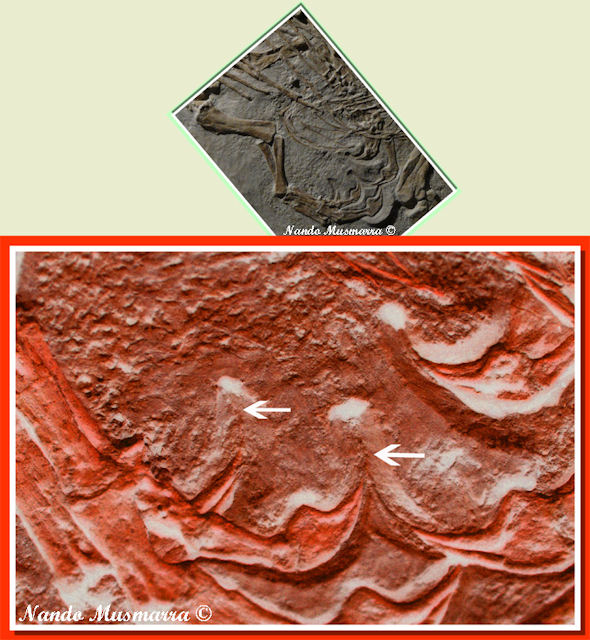

The rounded dermal scales preserved along the tail vertebrae hint at a basal coelurosaurian skin structure - Photo by Nando Musmarra

Under UV light: some faded tiny filamentous integumentary structures (in red) were interpreted by Chiappe and Göhlich as protofeathers (Eichstätt Jura Museum).

1 - Göhlich U.B. and Chiappe L.M. (2006). "A new carnivorous dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Solnhofen archipelago".

2 - Göhlich U.B., Tischlinger H., and Chiappe L.M. (2006). "Juravenator starki (Reptilia, Theropoda) ein nuer Raubdinosaurier aus dem Oberjura der Suedlichen Frankenalb (Sueddeutschland): Skelettanatomie und Wiechteilbefunde".

3 Xu X. (2006). "Scales, feathers, and dinosaurs".

4 Butler R.J., and Upchurch P. (2007). "Highly incomplete taxa and the phylogenetic relationships of the theropod dinosaur Juravenator starki".

5 Hone DWE., Tischlinger H., Xu X., Zhang F. (2010) "The Extent of the Preserved Feathers on the Four-Winged Dinosaur Microraptor gui under Ultraviolet Light".

6 Chiappe L.M. and Göhlich U.B. (2010). "Anatomy of Juravenator starki (Theropoda: Coelurosauria) from the Late Jurassic of Germany".

7 Musmarra Nando & Ricketts Wendell - The Bürgermeister- Müller Museum (Solnhofen, Germany) and the CARLOS Project - soon to be published

Nando Musmarra ©