The Mermaid Song

The Taulanne sirenian site in France, one of the oldest in the world.

Text by Diana Fattori, photos by Nando Musmarra

In Castellane, a lovely French town in the Haute Provence region, there is a museum dedicated to…mermaids! Why am I mentioning such fanciful characters in a magazine about fossils? Well, because the museum specializes in…fossil ‘mermaids,’ coming from the nearby Taulanne locality, where some of the oldest fossil sirenians of the entire world are found.

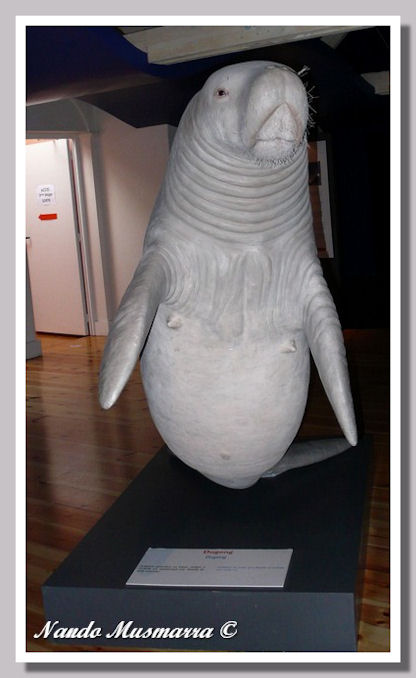

Painting of a mermaid inside the Musée Sirènes et Fossiles - Life-sized reconstructed model of a Dugong.

The museum exhibit starts by explaining myths and misconceptions about sirenians. Scientifically speaking, sirenians—also called sea cows—are an almost extinct group of aquatic herbivorous mammals. Most of us do not understand the link between sirenians and those mammals, but instead associate them with the idea of a woman with a fishtail who lures men to their doom with her long hair and enchanting songs. Why is that mysterious mythological creature, the “mermaid,” connected with the manatees and dugongs called sirenians?

Fantastic siren reconstruction by Spanish artist Joan Fontcuberta. Musée Gassendi, Digne, France

From ancient times, the myth of the siren has been very popular: immortal fishtail gods from Mesopotamia, Ulysses’ sirens, medieval illustrated books…all of them show diabolical characteristics of the sirens. Things changed during the Renaissance, when sirens became a symbol of eloquence, culture, and friendship. In the European popular tradition, fishermen and sailors used sirenians as decorative sculptures—good luck symbols—for their ships. Christopher Columbus, during his discovery trip to America, saw three “sirens;” they were manatees, shy and peaceful animals which have been considered to be ‘sirens’ for a long time. There is no doubt that manatees are at the origin of the siren myth. Other fabulous creatures find their roots from observations of nature; the Cyclops was created from the skulls of Mediterranean dwarf elephants, because the hole in the skull was considered an eye hole. In more recent times, the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen first, and Walt Disney later, transformed the perverse siren into an innocent girl.

Imaginary siren made of wood, dried fish skin and tail, claws and teeth of an unidentified animal - Musée Sirènes et Fossiles

Special kinds of sirens were created in England during the late 18th century: these were stuffed sirens, half fish and half wood sculpture, curiosity pieces exhibited together with other “freaks” like bearded women or not-so-tall giants. One of the more famous was the Fiji mermaid, exhibited in the Barnum Circus in 1842; another similar superstar was the Can Can mermaid from the Can Can theatre in Tombstone, Arizona.

One of the first descriptions of a living sirenian was made by the Spanish captain Gonzalo Fernando de Oviedo y Valdes in 1526. On his trips to America, he observed the West Indian manatees for a long time and he sketched several accurate drawings of those sea mammals, but “men of science” preferred to keep on mixing nature observation with the myth, and misinterpretation continued till the 19th century, when wiser scientists rejected the idea of sirens and created the scientific family of sirenians.

By the way, the myth never disappeared, and still today the media associates sirens with a beautiful woman emanating mystery and sex appeal. To attract customers, Starbucks, the American coffee shops company, chose the two tails siren as its logo.

Hand of a living Florida manatee (John Pennekamp State Park) - Complete hand from Taulanne site

In nature, the sirenian order includes four living species and two genera, and a third extinct genus (and consequently a fifth species). The two extant genera are Trichechus (manatee, three living species) and Dugong (dugong, one living species). Manatees live in fresh-to-brackish water of coastal rivers of Africa, the Caribbean islands, South America and the Atlantic coast of southern North America. Manatees have paddle-shaped tails and nails on their flippers. Dugongs are smaller than manatees and live the shallow waters of the Red Sea, the Western Pacific islands and the Indian Ocean. Their tail has fork shape. A third genus, Hydrodamalis (Steller’s sea cow) was the biggest of the sirenians, 26 ft long, and lived in coastal waters near the Bering Sea islands. It suffered from heavy hunting pressure and was exterminated about two hundred years ago, less than three decades after it had first become known to science.

Dugong, Metaxytherium floridanum, Clewinston Museum, Florida.

Early in the Paleogene, sirenians diverged from related ungulate mammals. Studies of their anatomy and fossil record demonstrate a close evolutionary relationship with proboscideans and the extinct desmostylians (hippo-like mammals). Like whales, sirenians evolved from land-dwelling mammals and have lost all superficial resemblance to their ancestors.

The oldest recorded sirenian fossil is Prorastomus sirenoides (Early Eocene, 50 million years old) from Jamaica. It had four limbs and spent its life in the water, but it was also able to walk on the land. This genus went extinct without a successor.

Snooty, a West Indian Manatee born in the old Miami Seaquarium on July 21, 1948 and arrived in South Florida Museum in Bradenton in 1949. He is the oldest manatee living in captivity.

Very early in their evolutionary history, sirenians became totally aquatic: in a few million years their body became more hydrodynamic, the skull moved closer to the body, the arms were transformed into flippers, legs disappeared, and the tail became horizontal for better propulsion in the water.

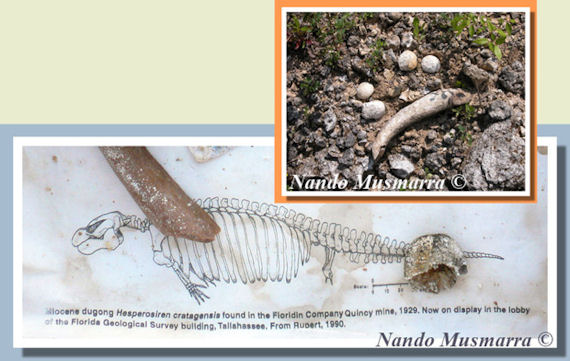

Fossil manatee ribs are a common find in Florida. Finds by PaleoNature.org Team

Sirenians’ ancestors occupied the warm and shallow waters of the planet; their fossils are found in Egypt (Protosirenae and Eosirenae), in Asia, North America and Europe (Prototherium and Halitherium), but their complete remains are few and far between. Usually, the most common sirenian fossil elements are limited to isolated vertebrae and ribs. Those dense and massive bones are not spongy and lack marrow cavities (a condition called pachyostosis). Ribs are easy to recognize by their banana-like shape; vertebrae have heart-shaped centra. Those fossils can’t usually be identified to the family level if they are collected out of stratigraphic context and isolated from limb and skull material. Also, fossil sirenian bones are very strong and durable and they are often “reworked,” that is, eroded out of the rock and incorporated into younger deposits.

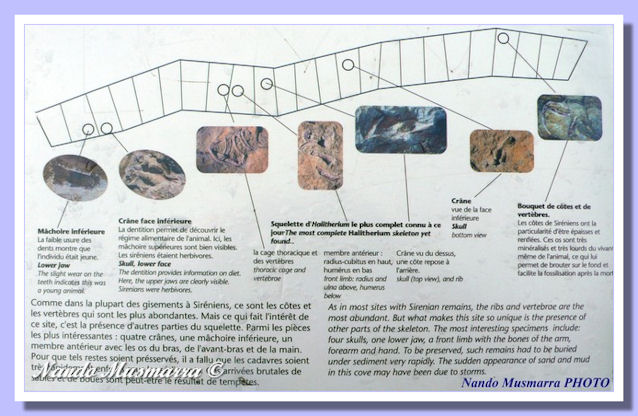

Underside of sirenian skull in situ, showing teeth - Vertebra and ribs

The Taulanne site near Castellane is especially important, because it preserves a group of several almost complete sirenian fossil skeletons. They are some of the oldest in the world, and for the first time, a complete hand/flipper was found. According to scientists, Taulanne fossils show an early stage of sirenian evolution, probably about ten million years after the first sirenian appeared on the planet, so those fossils are very important to understanding more about these not-too-well studied sea mammals.

The site was mentioned for the first time by the French palaeontologist Albert de Lapparent in 1938. The sirenian he found there he called Halitherium. Many years later, in 1994, Dr. Daryl Domning of Howard University in Washington, DC—one of the foremost experts on sirenian evolution—started to dig together with French paleontologists. This group of scientists supposed that from Taulanne, Halitherium spawned two separate branches of sirenian evolution: one containing the modern dugong and Steller’s sea cow, and the other leading to the three species of modern manatee.

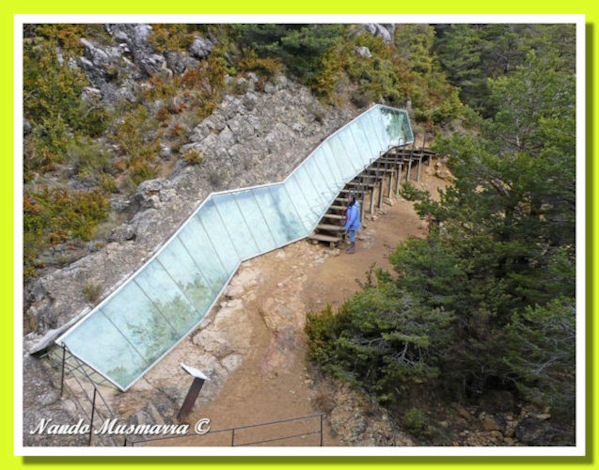

Taulanne fossil site - Interpretive sign for the site, in French and English - Photos by Nando Musmarra

At the site, seven complete skulls plus fragments were found (the bones found at Taulanne are exclusively sirenian), one of them belonging to a calf. Fossil skulls in good condition are important for identifying the different species and evolutionary groups. They also contain a wealth of information, such as details of the brain (from endocranial casts, scientists discovered that sirenians lost their olfactory lobes in the early evolutionary stages); nervous system, or diet (by analyzing their dentitions). Dugongidae and Trichechidae show very large differences in their dentitions. Teeth evolved in different ways because they adapted to different vegetable food available to the different sirenian families. Modern dugongs have four or five cheek teeth in each jaw (fewer in fossil forms). The teeth are heavy and bunodont with two transversely- curved crests, complicated by small cups resembling gomphothere teeth. Manatees have seven teeth present in each jaw at a time. Each tooth bears simple transverse crests and a posterior cingulum; upper teeth also have anterior cingula. Those numerous lophodont teeth develop at the back of the jaw and move forward into position during the animal’s life (this is called horizontal tooth replacement).

Study of the rocks at the Taulanne fossil site yields much information about the paleoenvironment. The presence of the microfossils Nummulites fabianus and Nummulites incrassatus dates the site back to 40 million years ago to the Middle Priabonian (Upper Eocene). Marine fossils like bivalves, gastropods, and crocodile’s teeth indicate a coastal environment. Corals in colonies show evidence of a reef in a shallow sea, very similar to the modern Caribbean. The Taulanne sirenians lived in a tropical paradise, grazing on sea grass, when a deadly storm (or huge tsunami wave) suddenly arrived.

Ribs from Taulanne - Thin section slab from Taulanne site. Note the many embedded bones.

The animals died quickly, and a mudslide was produced by the torrential water, carrying a huge amount of sediment. The bodies were covered very fast by sand and gravel, protecting them from scavengers. After 40 million years, the fossils are wonderfully preserved, mostly of them fully articulated. The bones are pink in colour, due of the presence of a phosphate compound.

Very often, special paleontological sites of a small size are fully excavated, and then the fossils are carried into the museum for further studies. The Taulanne site was graced with a different destiny. Many institutions asked to preserve the fossils in place as they were found, so everyone could enjoy this exceptional treasure. The site is included in the Haute Provence Geologic Preserve, where it is open for visits by the general public, and a marked trail leads visitors to the fossil area.

Fossil dugong – Le Maison du Parc, Apt, France.

The sirenian French specialist Claire Sagne assigned the Taulanne fossils to a new dugong species: Halitherium taulannense. The species was created by studying the remains of one perfectly-preserved skull, mandibles from two different animals, and one complete hand. Halitherium taulannense is the 16th scientifically described specie of sirenian from the Eocene.

While France preserves some of the older sirenian fossil remains, and Miocene sirenian sites are very common in the Southern Europe (more occasional are Pliocene remains), in the whole Mediterrannean Sea nowadays, manatees are totally extinct. Their disappearance is still an unsolved mystery.

Tail of Florida manatee injured by a boat.

Scientists suppose that long-term global environmental changes influenced their extinction, but maybe man played an important role as well. The slow and shy sea mammals couldn’t fight against years of heavy hunting and pollution, so they disappeared. Forever.

This old stamp from Niger publicizes sirenian protection.

Bibliography

Floquet Marc, Floquet Nicole, Guiomar Myette, Marchand Didier, Lamotte Didier: Le Gisement Fossilifére a Dugongs (Siréniens) du synclinal de Taulanne: hécatombes, tsunamites/tempestites, enfouissement, Livret guide de l’excursion géologique, 2007.

Guiomar Myette, Gomez-Passamar Nadine, Silvestre Jean-Pierre, Catalogue Castellane Musée Sirenès & Fossiles, Reserve Géologique de Haute-Provence, 2004.

Hulbert Richard C. (ed), The Fossil Vertebrates of Florida, University Press of Florida, 2001.

Diana Fattori © 2009

This article was published on Fossil News Volume 15, Number 12 — Dec, 2009