Bolca Aquarium in Stone - Big guys swam here!

Italian masterpieces to rival any da Vinci or Michelangelo

Text by Diana Fattori

Photos by Nando Musmarra

Paleoart by Loana Riboli

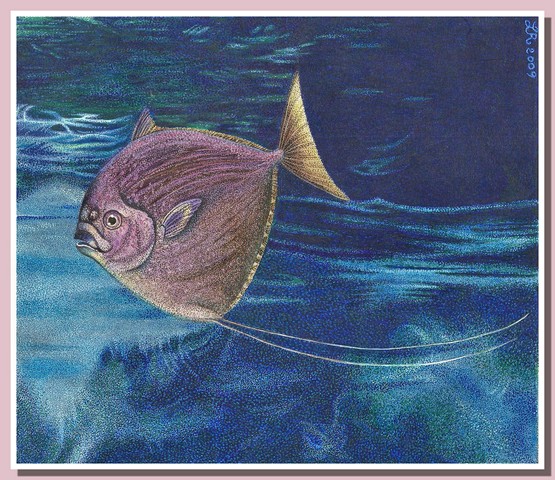

Mene rhombea - Paleoart by Loana Riboli

In North-East Italy, not far from Aviano AFB, lies the Veneto region with its famous cities: the sophisticated Venice, suspended on the water with its churches glittering gold and glass studios, the elegant Padua , preserving the Scrovegni Chapel painted by Giotto at the beginning of the 4th century and the University where Galileo taught, the romantic Verona, close to Garda lake where the young Romeo suspired under Juliet’s balcony in Shakespeare’s masterpiece.

Half an hour’s driving north from Verona there is Bolca, the tiny town famous worldwide for its Eocene fossil beds.

Mene rhombea (Volta, 1796). This moonfish is closely related to the recent Mene maculata living today in the Pacific Ocean

The first-documented record on Eocene Bolca fossils was the report done in 1555 by Italian botanist Pietro Andrea Mattioli. Since then Bolca fossils, especially extralarge fishes, became famous and scientists, amateurs, and people who like beautiful objects—and could afford them!—wanted at least one specimen in their collection.

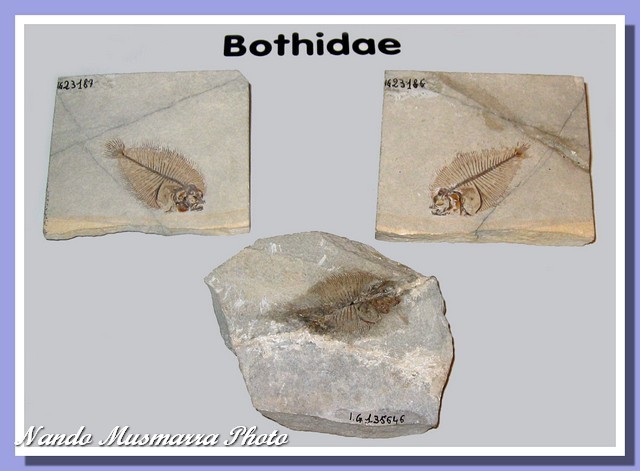

Eobothus minimum (Agassiz 1834–1842) - Paleoart by Loana Riboli - Bottom-dwelling predator related to recent flounders

Even Napoleon got the “Bolca fever,” and before leaving Italy on his way back home as conqueror he fell in love with those fishes of unusual size and incredible beauty. So he confiscated and exported to France, together with Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and many other Italian masterpieces, several hundred fossil fishes belonging to the huge private collection of Count Gazzola. Rumor says that Count Gazzola was asked to sign the “voluntary donation” with a gun pointed at his head…

Eoplatax papilio (Volta 1796). This extinct predator is related to recent batfishes of the genus Platax living in warm water.

The old literature used to consider Bolca fossils as one of the many evidences for Creationism: stone fishes were found on the mountains because of the Flood. During the centuries, those extraordinary fossils enriched the collections of many fine natural history museums in Italy and around the world— Paris, London, Vienna, Zurich, New York, Washington and Moscow—as the private collections of powerful men like Pope Sisto V and Canossa Cardinal, who owns the first huge angel fish specimen Eoplatax papilio.

Massimo Cerato at Bolca Fossil Museum. Note the size of the angelfish Eoplatax papilio

All the fossils come from four different mines in the Bolca mountains: the Pesciara, Monte Postale, Monte Vegroni and Purga of Bolca. The Pesciara (it means “fishes’ place”) is the so-called Monte Bolca locality in many reports, and is probably the most famous of the quarries because of the large amount of fishes excavated.

Sphyraena bolcensis (Agassiz). This predator is closely related to recent barracudas of the genus Sphyraena represented by 18 species living in tropical seas.

The Monte Postale produced huge fishes (the angel fish Eoplatax, the barracuda Sphyraena and the sting ray Narcine). In this fossil site fishes are often found disarticulated with their loose scales close to the body, suggesting decomposition due to a poor preservation environment.

Monte Vegroni is world-famous for its fossil palms (Eolatanites, Phoenicites and Morinda) and turtles.

Complete fossil palm Phoenicites wettinioides (Massalongo, 1858) - Fossil palm Latanites praticinensis

Purga of Bolca is the locality where in 1946 was discovered the rare fossil crocodile Crocodylus vicetinus, 1.85 meters long. The last two localities furnished all the palms dug during the second half of the 19th century, when lignite mines were still active.

Bolca fossiliferous limestone is dated back to the Lower Eocene (50 million years ago) at Pesciara and Monte Postale. Studies on microfossils consider Purga of Bolca and Monte Vegroni to be Lower Eocene, but some scientists disagree, placing those two locations to the younger Middle-Upper Eocene, according to their stratigraphic position.

Eocene swordfish ancestor - Paranguilla tigrina (Bleeker 1864). Extinct predator perhaps distantly related to recent moray eels.

From that exceptional area, originally mined for construction stones, and since 1817 investigated exclusively for fossils, were identified at least 300 fish species—for comparison, the Green River Formation barely counts several dozen different species—making Bolca one of the richest fossil deposits in the world. Besides fishes, Bolca also preserves many fine floral and faunal specimens—crustaceans, insects, molluscs, and plants— very similar to modern ones.

Trygon muricata (Volta, 1796) 60 centimeters in length (1.97 feet) - Torpedo sp. - probably related to recent electric rays of the genus Torpedo, represented by 13 species in modern seas.

During 500 years of digging activity, more than 100,000 fossils were extracted. However, it is not possible to compare Bolca to fossil Lagerstätten from Lyban and Wyoming: in Bolca there was no catastrophic event, nor do any of the four sites show evidence of mass mortality. The most reliable theory is that fishes died and fossilized at different stages, during a period of time spanning from very few to a thousand years. The Pesciara sites includes five fossiliferous levels, each of them composed by hundreds of strata made of hundreds of square meters linked to a unique sedimentation event.

Galeorhinus cuvieri (Agassiz 1835), fast swimmer shark closely related to recent representatives of the genus Galeorhinus

Paleontologists approximately found just one fish each ten square meters in one single stratum, too poor a haul for mass mortality. It is important to note that the fossil quarries do not represent the real Bolca fossils’ living habitat; they are just the “final destination,” the place where all the organisms—fishes, plants, insects—went after their death. Paleontologists are still debating if Bolca fishes died of natural causes—illness, old age, predation—or from single events like a red tide.

Eoplatax papilio

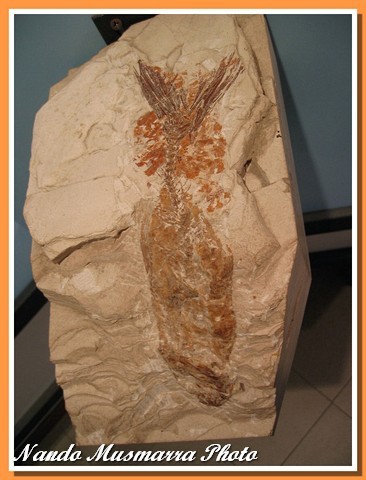

Most of the Bolca fossils show complete anatomical connection of the bones because they reached the sea floor very fast and necrophagus organisms didn’t feed on organic parts of the fishes because of the total lack of oxygen and very high salinity of the water. Occasionally the fishes hit the floor slowly, floating with the help of decomposition gases in their belly; others hit the ground really fast, even penetrating the sediment. This unusual fossilization suggests that the seafloor was “soft,” like the consistency of sour cream.

This fish fossilized in thick-creamy consistency seafloor, penetrating into sediments.

Most of the Bolca ichthyofauna has modern relatives, and they represent the oldest evidence of a modern association of temperate and sub-tropical coastal water environment.

Paleontologic and sedimentologic studies give us a good picture of what the Bolca area looked like during the lower Eocene; there were several different habitats: a huge emergent land as evidenced by terrestrial plants (coconuts, grass-like plants, shrubs) and animals (turtles and insects), a clearwater environment including rivers and ponds where fishes and plants (Eichorniopsis, Crassipes, Maffeia) lived together with dragonflies—whose larvae need stagnant waters to reproduce— and beaches, dunes, barrier islands, swamps, and open sea habitats.

Exellia velifer (Volta, 1796). Extinct fish feeding on plants

Most of the Bolca fish species exhibit important analogies with living species from a modern coral reef; that’s why paleontologists call Bolca fishes by both their scientific and common names, the same used today by fishermen— angelfish, barracuda, lookdown, and sailfish, for example. Because of those fishes, Bolca was always considered as a coral reef environment, but paleontologists are still searching, because after years of digging no reef has yet been found.

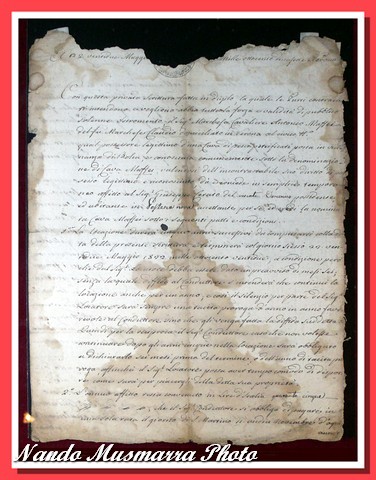

Bolca Rock Shop and 1817 Pesciara quarry rental agreement by Giuseppe Cerato, ancestor of Massimo Cerato. For 45 £ (barely 30cents) each year plus several fossil fishes the Cerato family paid the rental to Mr. Massalongo, the old owner. In 1859 the Ceratos bought the Pesciara.

Since 1770, all the fossils have been dug by the Cerato family on a regular basis. As artisans preserving a special tradition, the Ceratos handed down from father to son for seven generations the job of “fossil fishes digger.” In the last few years Erminio (the father) and Massimo (the son) gained international acclaim for the site because of their incredible discoveries. They were rewarded with a very special fish named after their family name: Ceratoichthys pinnatiformis.

Ceratoichthys pinnatiformis (Blot, 1969). This extinct open-water fish is 50 centimeters in length. Verona Civic Museum of Natural History

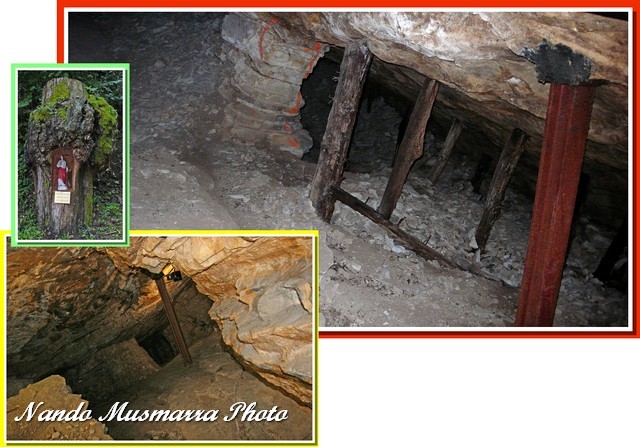

From 1999 to 2008, the Verona Civic Museum of Natural History organized the yearly dig season at Bolca fossil beds, finding 3313 specimens, five of them new species. After three centuries the scientific dig still follows the original Ceratos’ method: like old miners, researchers dig galleries in the hard limestone, creating holes and tunnels to reach the fossils. To protect men’s lives in the mines, both concrete and wood supports are situated in sensitive locations. Wood supports are especially useful: in the event of movement of the ceiling, they warn with squeaks more eloquent than a thousand words!

La Pesciara, the quarry caves dug out to retrieve the fossil fishes - Note the wooden timbers used to shore up the roof

In 1969 in Bolca was established the Museum of Natural History, managed by the Cerato family. The museum, totally renovated in 1996, preserves some of the finest fossils found in recent years. Right at the entrance seven exceptional fossil fishes welcome visitors, all of them from Pesciara. Exhibited in special showcases, the specimens are so pretty that they can be compared to jewellery pieces. The museum offers a glimpse of the area’s fossils also from several other localities near Bolca, and the star of the show is the wonderful collection of fossil fishes hosted on the second floor: it is impossible to describe the beauty and uniqueness of the fossils displayed here. Sharks, enormous angel fishes, super-detailed rays, whole palms with trunks, leaves and fruits are preserved as if they were printed on the rocks. In my opinion no Eocene fauna can hold a candle to the perfection and beauty of the Bolca fossils

.

Eoplatax (Blot, 1969) subvespertilio - Verona Civic Museum of Natural History

While in the area it is a very interesting side trip to the Pesciara, the famous quarry rich in fossils. The Pesciara is very different from the Green River quarries in Wyoming. It isn’t an open quarry where the wind blows in your hair, but it is dug inside the mountain. Pesciara is an historic quarry, worked slowly year by year for almost three centuries. The visit presents no problem; working in the narrow tunnel is another topic: members of the Cerato family obviously never suffered from claustrophobia!

Exellia velifer - Verona Civic Museum of Natural History

Since 1990, the Bolca beds and the museum are included in Lessinia Natural and Regional Park.

Many thanks to Massimo and Erminio Cerato (Bolca Museum and Pesciara quarry), Diego Lonardoni (Lessinia Regional Natural Park), Roberto Zorzin (Verona Civic Museum of Natural History) and his son Alessandro for kindness, open doors, and info.

All fossils are from Bolca Museum except as noted.

Three generations of Cerato's family showing a freshly discovered fossil fish.

Diana Fattori © 2009

This article was published on Fossil News Volume 16, Number 9 — November/Dicember, 2010